How ’90s Country Music Became Nashville’s Dominant Sound – Vulture

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Getty

In 1996, Jo Dee Messina’s debut single, “Heads Carolina, Tails California,” shot up the charts. It was an archetype of the era’s sound, slipping traditional-country signifiers like mandolin, steel guitar, and organ into a pop-oriented anthem with a hefty chorus. (The song peaked at No. 2 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles chart, behind Brooks & Dunn’s “My Maria,” another of the era’s definitive hits.) Tim Nichols and Mark D. Sanders’s lyrics told a crisp, affecting love story about a couple skipping town together — “We’re gonna get out of here if we gotta ride a Greyhound bus / Boy, we’re bound to outrun the bad luck that’s tailin’ us.” “There were a lot of great story songs in the ’90s,” Messina tells me. “And people relate to a story.”

Those stories drew thousands of fans to country music in the ’90s, including a young Cole Swindell. Growing up in southwestern Georgia, he loved George Strait, Reba McEntire, and Tim McGraw. “It literally was every artist,” says Swindell, now 40. “I remember being able to relate to songs, just knowing that, Man, that’s pretty crazy, somebody else out there knows how this feels.” After he became a singer and songwriter years later and bagged his first few No. 1s, he felt compelled to write an ode to the music he grew up with. Interpolating “Heads Carolina” wasn’t his idea — Rusty Gaston, CEO at Sony Music Publishing Nashville, suggested it knowing Sony already owned a cut of the publishing. Swindell and his co-writers spun it into “She Had Me at Heads Carolina,” their own story song, where a guy falls in love with a girl after watching her sing Messina’s version at karaoke. On the record, you can hear Swindell grinning as he croons, “She’s a ’90s country fan — like I am.”

Who isn’t right now? In Nashville, the style of the ’90s hasn’t been this cool since, well, the ’90s — the era when country finally figured out how to balance its dueling impulses toward old-fashioned integrity (fiddles, steel guitar) and mainstream appeal (pop-oriented hooks). “Millennial or Gen-Z artists, of course they know who Waylon Jennings is and Hank Williams is, but they’re not thinking about those people as the legacy artists for their generation,” says Taylor Lindsey, head of A&R at Sony Music Nashville. “They’re thinking about the Jo Dee Messinas and the Tim McGraws and the Sammy Kershaws.”

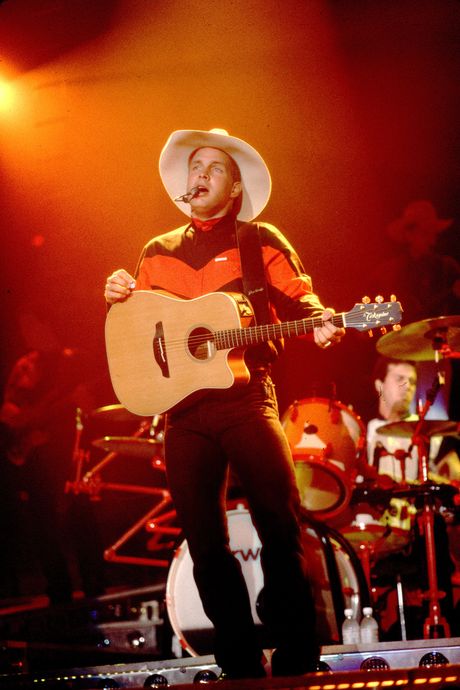

From left: Shania Twain in ‘96; Garth Brooks in ‘93 Photo: Paul Natkin/WireImagePhoto: Paul Natkin/WireImage

From top: Shania Twain in ‘96; Garth Brooks in ‘93 Photo: Paul Natkin/WireImagePhoto: Paul Natkin/WireImage

That’s all happening on top of splashy returns from a few of the period’s biggest names. May’s ACM Awards were co-hosted by Garth Brooks, while his wife and fellow ’90s star, Trisha Yearwood, dueted her biggest hits with a new torchbearer, Carly Pearce. Luke Combs sang the sentimental, fiddle-led ballad “Love Me Anyway,” which sounds like a lost Alan Jackson or Vince Gill cut. Hailey Whitters, winner of New Female Artist of the Year, did “Everything She Ain’t,” a song indebted to the Chicks’ 1998 album Wide Open Spaces — both the plucky sound of “There’s Your Trouble” and the lyrical come-ons of “I Can Love You Better.” Oh, and one of the night’s biggest winners? “She Had Me at Heads Carolina,” which took home Song and Single of the Year. “Jo Dee, we wouldn’t have this song without you making the original song a hit,” Swindell said when he accepted his first trophy.

Technically, ’90s country began in 1989, the year four confident performers who would define the next decade (and beyond) in the genre debuted on the charts: Garth Brooks, Alan Jackson, Clint Black, and Travis Tritt, known as the “Class of ’89.” “Their distinctive voices and nuanced music — at once undeniably modern and deeply rooted in the genre’s past — showed the world there was more to country music than overalls and tobacco spit,” the Tennessean declared in a 30th-anniversary reflection from 2019.

The Class of ’89 arrived during a major authenticity crisis in the genre. Many artists thought the genre needed to be taken back after the soft “urban cowboy” crossover hits of the late ’70s and early ’80s, from artists like Kenny Rogers and Mickey Gilley. In response, artists like Strait, Reba, and Randy Travis led a neo-traditional wave, defined by a return to a rootsy western sound (swaying songs full of fiddle and steel guitar) and flaunting your country bonafides. The Class of ’89 aimed to build on that, turning the twangy classic sound into broadly appealing, stadium-ready hits with — even if they wouldn’t want to admit it — a pop sensibility. (By 2000, Jackson was lamenting the death of “tradition” in “Murder on Music Row,” a duet with the genre giant George Jones.) The songs excelled both in their sharply detailed, character-driven storytelling and the universality of the feelings. Like Jackson once sang, it was “a lot about livin’ and a little ’bout love.”

To the songwriter Josh Osborne, the attraction was simple: “The thing with ’90s country was every song felt huge,” he says. He remembers listening to John Michael Montgomery’s love songs as a teenager in Kentucky, and later arriving in Nashville at the end of the decade, when Martina McBride’s country-pop blend on Evolution was the talk of the town. The songs were obviously country, but they had sturdy pop bones: clear vocal performances, relatable lyrics, simple and catchy choruses. After years of anxiety about identity and commercial viability, country sounded like a genre that knew where it was going.

You could see it on the charts too, after Billboard began using Nielsen SoundScan to track sales. The previous method of manual reporting from record stores had been imprecise and easily manipulated, and the shift meant the popularity of genres like rap, country, and alternative rock was finally being reflected. Brooks soon became the first country artist to debut at No. 1 on the “Top Pop Albums” chart when his third record, Ropin’ the Wind, sold 400,000 copies (and went on to be certified 14-times Platinum before the end of the decade), and would later log three more No. 1, Diamond-certified albums (The Chase, In Pieces, and Sevens). Brooks wasn’t alone putting up those numbers either. Shania Twain had found crossover success beginning with her 1995 album The Woman in Me (12-times Platinum), and continuing through 1997’s Come on Over (two-times Diamond), buoyed by the hit “You’re Still the One.” Brooks and Twain became even better known for impressive live shows — Brooks’s 1994–96 world tour was among the decade’s highest-grossing in any genre, while Twain’s 1998–99 Come on Over tour was the highest-grossing of a female country artist.

Twain opened the doors for country’s women to succeed on the pop charts in the latter half of the decade, including Faith Hill, who hit No. 7 with “This Kiss” and No. 2 with “Breathe,” and LeAnn Rimes, whose version of “How Do I Live” also hit No. 2. (Later into the 2000s, the Chicks and McBride would follow.) Labels helped by releasing “pop” remixes and radio edits that swapped banjo and fiddle for more palatable electric guitar, but these songs started as definitively country, from the foot-stomping fiddles on Twain’s songs to the steel guitar holding up Hill’s. After decades of arguing over how pop or country the genre should be, it sounded like country music found an answer: Why not both?

About a decade ago, Osborne remembers talking with other songwriters about how “underrated” some of those ’90s songs were. “Somebody would come in and be like, ‘Man, you remember “Alibis,” by Tracy Lawrence? What a great song,’” he says.

By then, the sound of the ’90s had long since fallen, after country pushed the needle further toward pop. Artists like Bon Jovi and Kid Rock scored crossover hits in the early aughts; by the end of the decade, some of the genre’s biggest forces appealed far beyond country, like Taylor Swift and Carrie Underwood. That set the stage for the “bro-country” that dominated the 2010s: hip-hop influenced party songs that incited a love-’em-or-hate-’em response in Nashville and beyond. Yes, the sound made country a massive commercial force once again, thanks to hits by Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, and Florida-Georgia Line — like their 2013 song “Cruise,” one of country’s best-selling singles ever. But many musicians and writers quickly tired of the genre’s snap-tracks, misogyny, and stereotypical lyrics about beer and trucks. Throwing it back to the ’90s started to seem like returning to more authentic roots. “Bro-country was so much about getting back to the country: ‘We’re ridin’ on the back roads. We’re sittin’ in the woods,’” says Osborne, noting he’s even written for bro-country giant Sam Hunt. “I think people started having a response of, ‘Okay, but let’s get back to country music.’ It wasn’t just about being in the country. It was more about life, and it was about love, and all that kind of stuff.” (Not that bro-country is fully dead, either, thanks to the massive popularity of Morgan Wallen and recent return of Jason Aldean.)

At the same time, enough time had passed for ’90s music to begin getting canonized. It was happening all over culture: Hip-hop was reviving the decade’s hits through samples, magazines pulled hot fashion trends from the decade, and TV shows like Saved by the Bell and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air were rebooted. Soon, you could hear Garth Brooks on the classic country stations, watch bands cover Tim McGraw and Jo Dee Messina at country bars, and witness Alan Jackson be inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. “Fast Car” may be from 1988, but Luke Combs’s breakout Tracy Chapman cover was motivated by that same impulse, to pay homage to what he grew up with.

For Hailey Whitters, 33, it was just whoever she heard on the radio in Shueyville, Iowa, when she was younger. “Growing up in small-town, rural Iowa, the radio was really my only source for music,” she says. “I didn’t come from a super-musical family, my parents weren’t really playing a bunch of records around the house, so for me, my whole introduction, and I guess education in country music was what I was hearing on the radio.” She still remembers being in the car with her mom at the post office the first time she heard “Wide Open Spaces” by the Chicks — a song she often covers live today.

Landslide: The Chicks cleaning up at the Grammys, 1999.

Photo: SGranitz/WireImage

Whitters’s songs draw heavily from the ’90s with a penchant for banjo and fiddle in songs like “Everything She Ain’t” and clever, punchy choruses that have become a hallmark of her writing on songs like “Dream, Girl” and “Plain Jane.” (She further honored her ’90s influence on a summer EP, I’m in Love.) “That’s the stuff I was raised on — that’s what I thought you had to do, you know,” she jokes of her hook writing. But the biggest thing she took from the era was simply seeing so many prominent women in country music — mononyms like Shania, Faith, Trisha, and Martina. “It makes me sad for future generations that they’re not hearing so many females on the radio,” she says. “It’s such a reason I’m here, is getting to hear my perspective, or those songs that felt like me.”

It’s no coincidence that the return of the ’90s influence is happening as artists like Shania Twain and the Chicks are themselves returning to the spotlight — and prompting reevaluations of their legacies. In a 2019 interview with the Guardian, Taylor Swift said she didn’t speak out about politics after being warned not to “be like the Dixie Chicks,” who were banned from country radio after protesting the Iraq War in 2003. That, along with the Chicks releasing their first album in 14 years, Gaslighter, in 2020, sparked a conversation about the reverberations of their ban, and country radio’s lack of support for women at large. Meanwhile, for Twain, a 2022 documentary, Not Just a Girl, explored the ways she was judged in the ’90s for being too pop for country and expressing her sexuality on stage. Now, Twain is building on that attention with a new album, Queen of Me, a bubbly collection of songs with some of the playful sparkle of her earlier pop-country hits. She spent much of the year touring with a slew of her torchbearers as openers, including Kelsea Ballerini, Breland, and Whitters. For a girl whose mom used to sneak her into the local bar to karaoke “Any Man of Mine” and who once dressed as Twain for Halloween, it was a full-circle moment. “That was the first bug for me, as far as performing in public: wanting to be Shania and wanting to be the way that I felt in those songs,” she says.

Their influence has even crept past the boundaries of country music. In 2018, the indie-rock supergroup boygenius did a popular cover of the Chicks’ “Cowboy Take Me Away” for the radio station KEXP; last year, Harry Styles brought Twain out for a duet of “Man! I Feel Like a Woman!” and “You’re Still the One” during his Coachella performance. The singer-songwriters Katie Crutchfield and Jess Williamson, who both came up in indie music, had never fully embraced their love of country in their own music until they began working on an album as a duo, Plains. They began bonding over the ’80s and ’90s country music they once loved, like Bonnie Raitt, Lucinda Williams, and the Chicks. With songs like the album’s title track, “I Walked With You a Ways,” Williamson, 35, challenged herself to write in both a specific and relatable way — the difficult balance that defined many ’90s songs. “I really went into it thinking, How can I write a song that is going to touch something within a lot of people?” she says. “Because something like love and loss is so universal.” It’s a lesson she says she’s carried over to the western-tinged solo album she released this year, Time Ain’t Accidental.

Heads 1996, Tails 2023: Swindell and Messina perform at the ACM Awards.

Photo: Rich Polk/Penske Media via Getty Images

As an artist outside the country industry, where country can be looked down upon as lower class or generic, Williamson admits she once “rejected” country and folk music. But she says something changed around the pandemic. “I lost all patience over the last couple of years for pretension and snootiness and exclusivity, and I’m so much more interested in something that’s just gonna feel good,” she says. And she’s not the only one who has noticed it, either. Lindsey, the A&R head, notes that many ’90s country songs themselves have “a huge sense of nostalgia.” “Through the course of the past two and a half years, feeling completely burnt with everything that’s been going on culturally and socially, when you want to escape, what do you do? Where do you go?” she says. “You always try and find those things that feel safe or feel good or remind you of better times.”

That’s been the biggest joy of watching country’s current ’90s nostalgia play out, especially if you grew up with the music yourself. At last year’s CMA Awards, one of the hands-down highlights was Jo Dee Messina’s surprise appearance at the end of Cole Swindell’s performance of “She Had Me at Heads Carolina.” Her presence was electric from the moment she stepped on stage, belting a verse of her original and unable to contain her smile. Messina was happy to make the moment happen, even if it meant messing with her tour schedule and sneaking over after the red carpet. She knows she could’ve taken the rise of “She Had Me at Heads Carolina” differently, like she even saw others doing. “Sometimes, I think, at the beginning, in my circle, people were a little bit distraught,” she says — they thought Swindell had messed with her version. “I just come from a place of gratitude.” Backstage, Swindell responded the same way. “She kept saying, ‘This is your moment,’” he remembers. “And I’m like, ‘No, this is our moment.’”

Source: News